In this article

- Text link

- Text link

Making and serving raclette is a fine art

The Gazette

FOOD

THE LIVING SECTION – MONTREAL – WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 28, 1987

By JAMES QUIG

Of the Gazette

NOYAN — Fritz Kaiser offered a choice of beverage.

“We can have tea or wine,” he said, holding up a chilled bottle of Chardonnay. “Either is very appropriate with raclette.”

I checked my watch and asked for the wine. It was almost one o’clock in the afternoon.

We were at Kaiser’s cheese factory in Missisquoi County, about an hour’s drive south of Montreal. I had come to study the Swiss art of making and serving raclette cheese.

You know about raclette, of course.

It’s on the same page as rabotte and ragoût in the Larousse Gastronomique.

Scraped off

Raclette, says Larousse, is a variety of Swiss cheese fondue that is a specialty of the canton of Valais, where “it is made by holding a big piece of the local cheese to the fire and scraping off the softened part as it melts.”

“The scraped-off cheese is put on a plate and eaten with potatoes in their jackets, not forgetting the accompaniment of the very heavy white wine of Valais.”

Frankly, that’s more than I ever knew about raclette. Somehow, I always thought of it as a skier’s dish. Something enjoyed on a mountain by rosy-cheeked people with reindeer designs on their sweaters.

And then, on a country drive, I spotted a sign that said: Fromagerie Fritz Kaiser. I have a soft spot for rural cheese factories, so I turned right at the corner and went in search of a Fromage Canadien snack.

But cheddar, it wasn’t. Fritz Kaiser had moved to Canada after graduating from a Swiss cheese school in 1978.

He was a raclette man — and there wasn’t a ski pole in sight.

Yes, he said, raclette was a dish that worked especially well in cool weather. But no, it didn’t require slopes.

Let’s clear up something else here, Fritz: Is raclette a distinct category of cheese or is it a way to serve cheese?

“It’s both,” he said, shaving off a sample slice from his wheel.

“I eat raclette seven days a week. Sometimes I melt it, sometimes I don’t.”

“What about your cholesterol count?”

He says he never counts it.

Mostly raclette

Kaiser, 28, makes 1,200 pounds of cheese a day here and most of it is raclette.

He also makes Noyan, a Tilsit-style cheese, and Cantic, a semi-firm cheese to which he adds fine herbs, garlic and peppers.

“The Noyan is very similar to the raclette,” he says. “But it’s more a cheese to eat than a cheese to melt.”

Noyan and Cantic are both delicious. But our business today is raclette. We’re here to melt.

“Taste,” he said, offering a slice off his raclette wheel.

I have never been to cheese school and know nothing of the cheese-tasting art.

Should I hold it up to the light and check it for color? Was I expected to sniff it and roll it around in my mouth before proclaiming it to be a perky yet unaggressive little cheese?

“Go ahead. Eat it,” said Kaiser.

I ate it.

“It reminds me of Oka cheese.”

The cheesemaker seemed pleased. Maybe even a little impressed.

“That’s right. It’s a semi-soft cheese. The label says it is surface-ripened, but actually it ripens in both directions — outside in and inside out.”

Correct vocabulary

It’s the kind of thing one likes to know — and use. Correct vocabulary means so much in these matters.

“I love your two-way cheese,” you say to the hostess.

“I beg your pardon?”

“It’s ripened in both directions,” you get to inform her. “Outside in and inside out.”

And then you move on to the smoked salmon.

Fritz and his wife, Christin, have promised to melt some raclette for lunch to show The Gazette team how it’s done.

They live in a farmhouse across the road, and Fritz’s day had started shortly after 6 a.m.

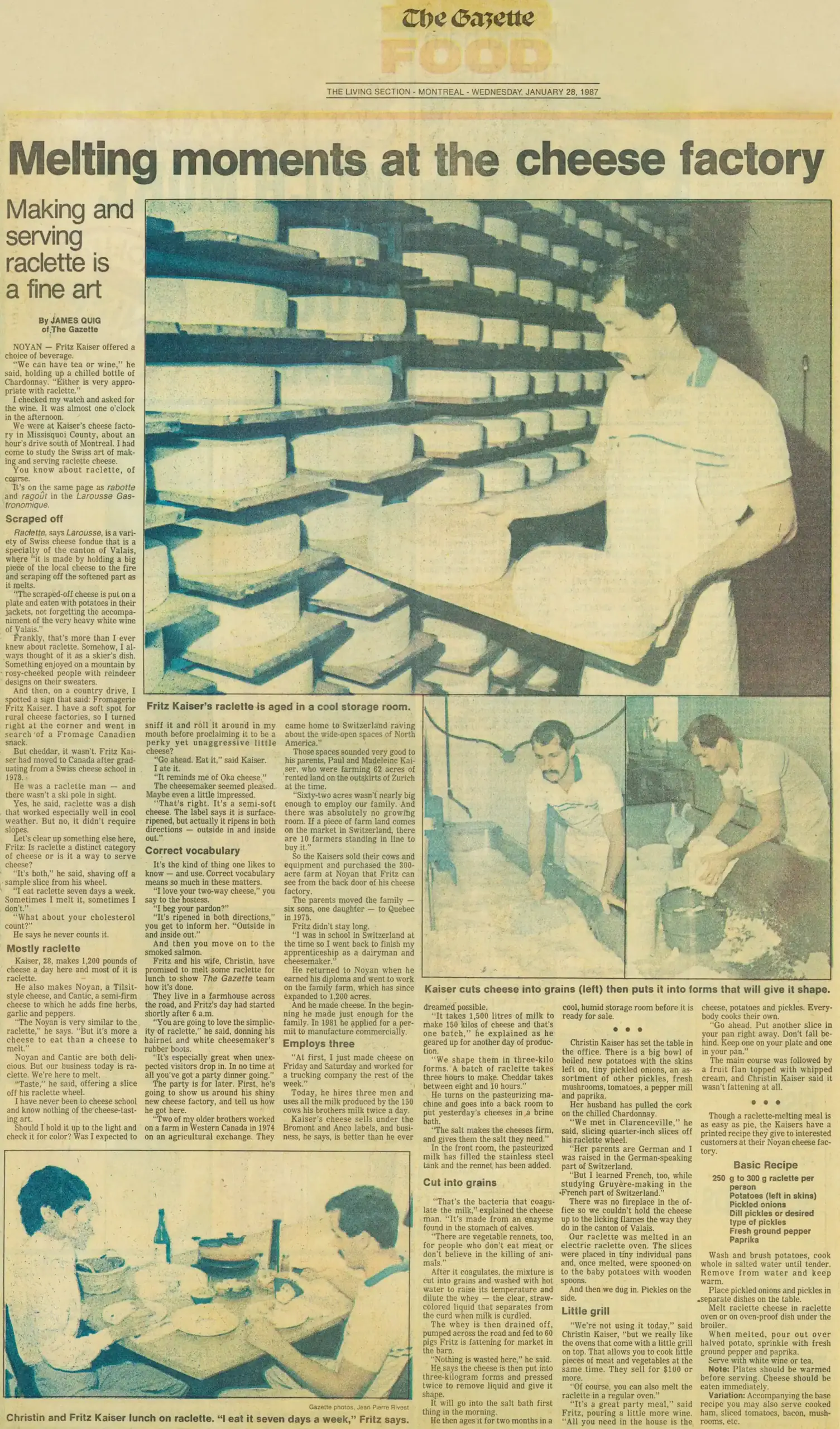

“You are going to love the simplicity of raclette,” he said, donning his hairnet and white cheesemaker’s rubber boots.

“It’s especially great when unexpected visitors drop in. In no time at all you’ve got a party dinner going.”

The party is for later. First, he’s going to show us around his shiny new cheese factory, and tell us how he got here.

“Two of my older brothers worked on a farm in Western Canada in 1974 on an agricultural exchange. They came home to Switzerland raving about the wide-open spaces of North America.”

Those spaces sounded very good to his parents, Paul and Madeleine Kaiser, who were farming 62 acres of rented land on the outskirts of Zurich at the time.

“Sixty-two acres wasn’t nearly big enough to employ our family. And there was absolutely no growing room. If a piece of farm land comes on the market in Switzerland, there are 10 farmers standing in line to buy it.”

So the Kaisers sold their cows and equipment and purchased the 300-acre farm at Noyan that Fritz can see from the back door of his cheese factory.

The parents moved the family — six sons, one daughter — to Quebec in 1975.

Fritz didn’t stay long.

“I was in school in Switzerland at the time so I went back to finish my apprenticeship as a dairyman and cheesemaker.”

He returned to Noyan when he earned his diploma and went to work on the family farm, which has since expanded to 1,200 acres.

And he made cheese. In the beginning he made just enough for the family. In 1981 he applied for a permit to manufacture commercially.

Employs three

“At first, I just made cheese on Friday and Saturday and worked for a trucking company the rest of the week.”

Today, he hires three men and uses all the milk produced by the 150 cows his brothers milk twice a day.

Kaiser’s cheese sells under the Bromont and Anco labels, and business, he says, is better than he ever dreamed possible.

“It takes 1,500 litres of milk to make 150 kilos of cheese and that’s one batch,” he explained as he geared up for another day of production.

“We shape them in three-kilo forms. A batch of raclette takes three hours to make. Cheddar takes between eight and 10 hours.”

He turns on the pasteurizing machine and goes into a back room to put yesterday’s cheeses in a brine bath.

“The salt makes the cheeses firm, and gives them the salt they need.”

In the front room, the pasteurized milk has filled the stainless steel tank and the rennet has been added.

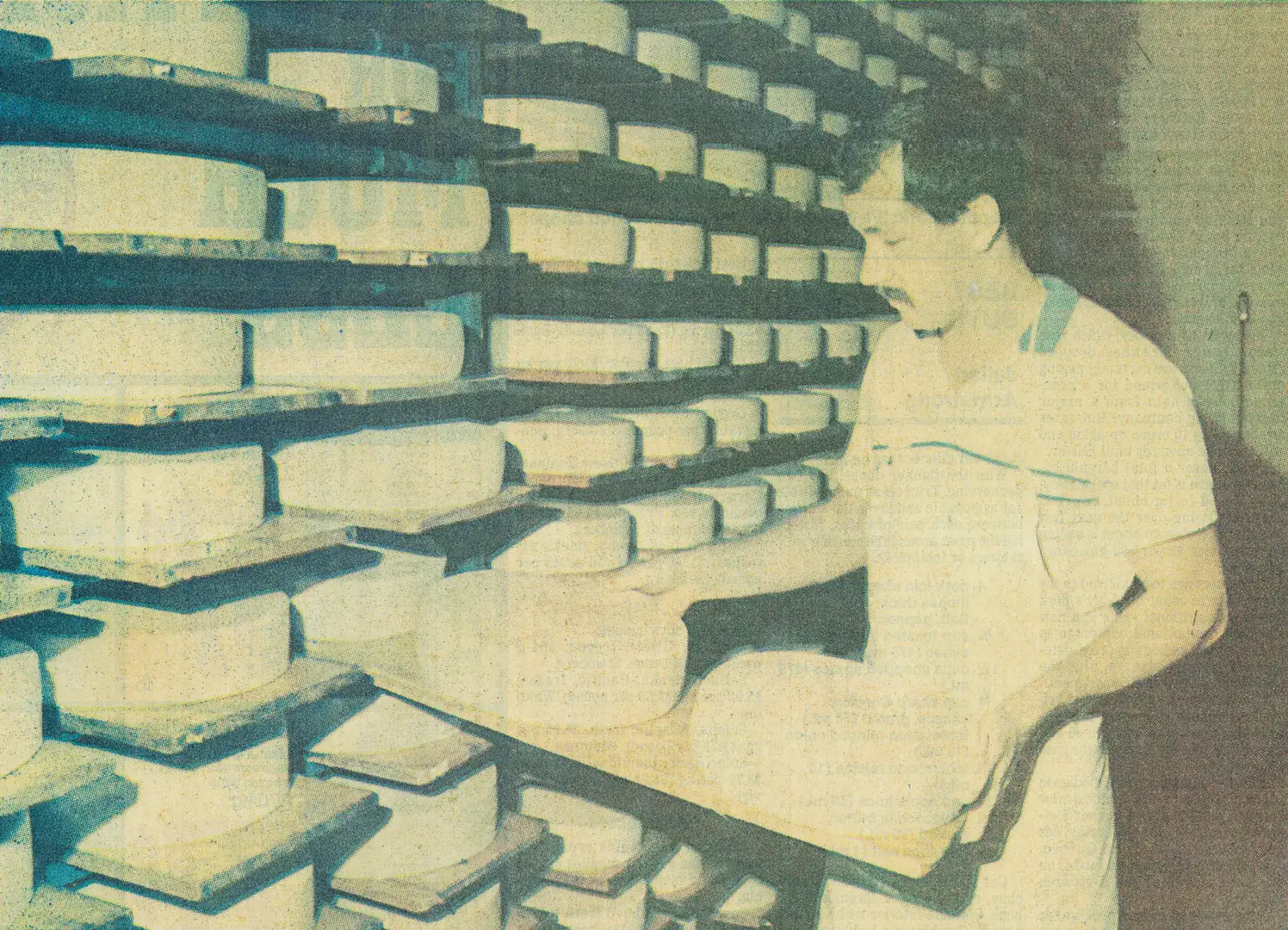

Cut into grains

“That’s the bacteria that coagulate the milk,” explained the cheese man. “It’s made from an enzyme found in the stomach of calves.

“There are vegetable rennets, too, for people who don’t eat meat or don’t believe in the killing of animals.”

After it coagulates, the mixture is cut into grains and washed with hot water to raise its temperature and dilute the whey — the clear, straw-colored liquid that separates from the curd when milk is curdled.

The whey is then drained off, pumped across the road and fed to 60 pigs Fritz is fattening for market in the barn.

“Nothing is wasted here,” he said.

He says the cheese is then put into three-kilogram forms and pressed twice to remove liquid and give it shape.

It will go into the salt bath first thing in the morning.

He then ages it for two months in a cool, humid storage room before it is ready for sale.

…

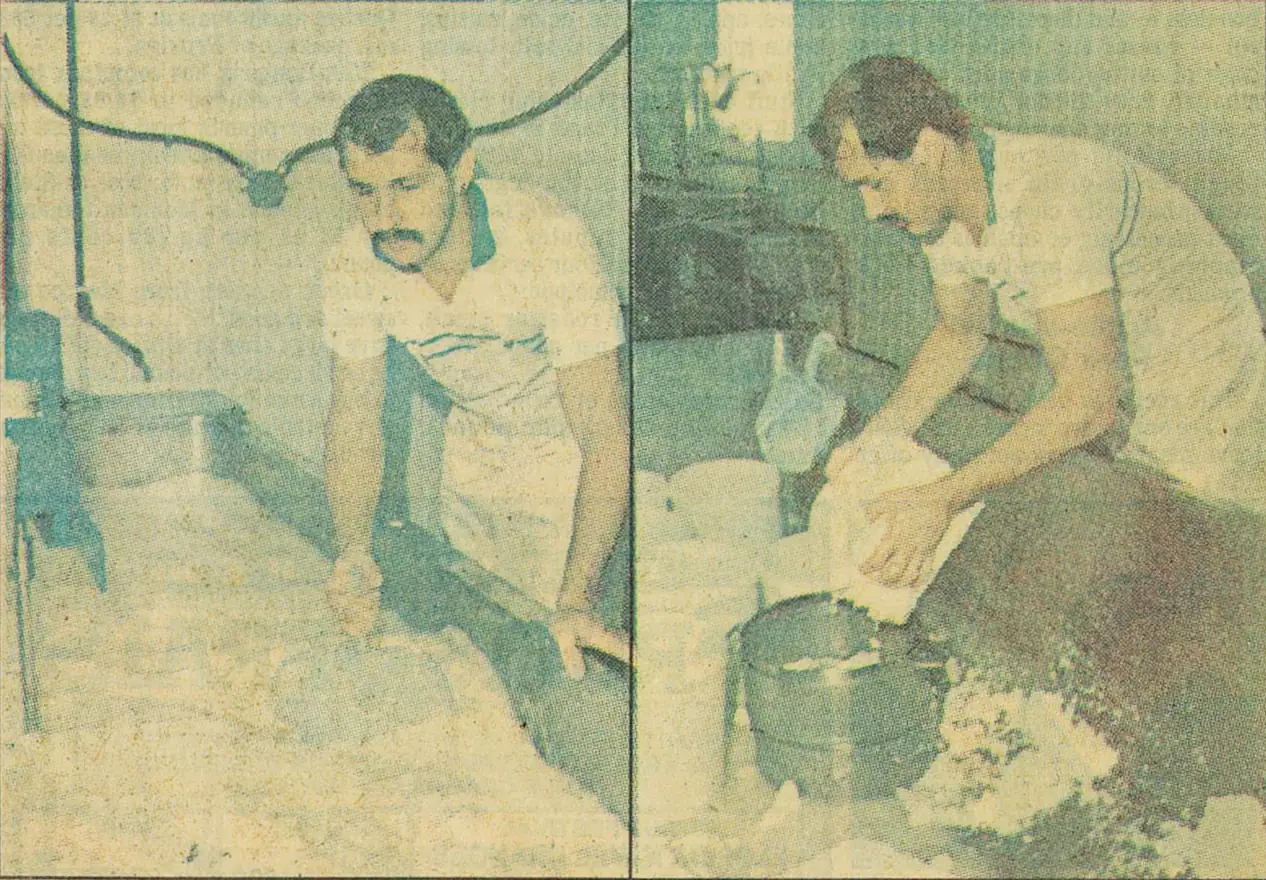

Christin Kaiser has set the table in the office. There is a big bowl of boiled new potatoes with the skins left on, tiny pickled onions, an assortment of other pickles, fresh mushrooms, tomatoes, a pepper mill and paprika.

Her husband has pulled the cork on the chilled Chardonnay.

“We met in Clarenceville,” he said, slicing quarter-inch slices off his raclette wheel.

“Her parents are German and I was raised in the German-speaking part of Switzerland.

“But I learned French, too, while studying Gruyère-making in the French part of Switzerland.”

There was no fireplace in the office so we couldn’t hold the cheese up to the licking flames the way they do in the canton of Valais.

Our raclette was melted in an electric raclette oven. The slices were placed in tiny individual pans and, once melted, were spooned on to the baby potatoes with wooden spoons.

And then we dug in. Pickles on the side.

Little grill

“We’re not using it today,” said Christin Kaiser, “but we really like the ovens that come with a little grill on top. That allows you to cook little pieces of meat and vegetables at the same time. They sell for $100 or more.

“Of course, you can also melt the raclette in a regular oven.”

“It’s a great party meal,” said Fritz, pouring a little more wine. “All you need in the house is the cheese, potatoes and pickles. Everybody cooks their own.

“Go ahead. Put another slice in your pan right away. Don’t fall behind. Keep one on your plate and one in your pan.”

The main course was followed by a fruit flan topped with whipped cream, and Christin Kaiser said it wasn’t fattening at all.

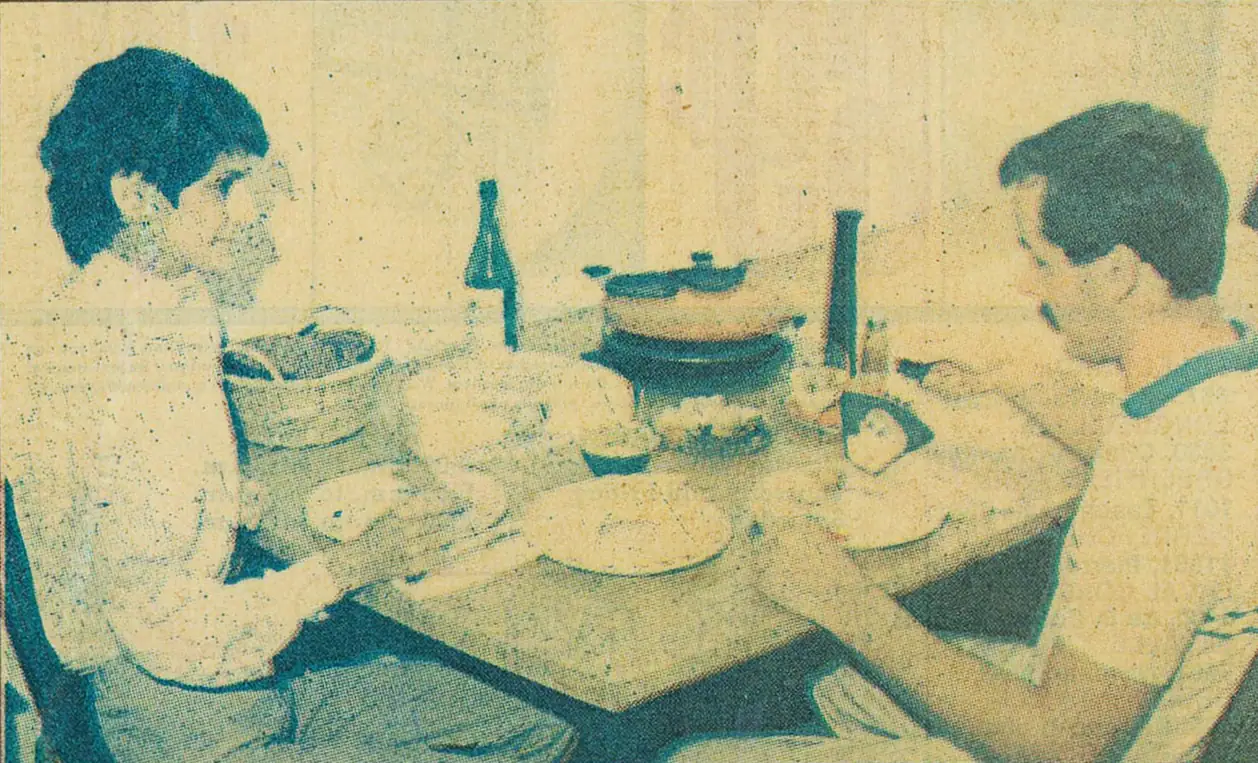

Christin and Fritz Kaiser lunch on raclette. “I eat it seven days a week,” Fritz says

Gazette photos, Jean Pierre Rivest

Basic Recipe

Though a raclette-melting meal is as easy as pie, the Kaisers have a printed recipe they give to interested customers at their Noyan cheese factory.

- 250 g to 300 g raclette per person

- Potatoes (left in skins)

- Pickled onions

- Dill pickles or desired type of pickles

- Fresh ground pepper

- Paprika

Wash and brush potatoes, cook whole in salted water until tender. Remove from water and keep warm.

Place pickled onions and pickles in separate dishes on the table.

Melt raclette cheese in raclette oven or on oven-proof dish under the broiler.

When melted, pour out over halved potato, sprinkle with fresh ground pepper and paprika.

Serve with white wine or tea.

Note: Plates should be warmed before serving. Cheese should be eaten immediately.

Variation: Accompanying the base recipe you may also serve cooked ham, sliced tomatoes, bacon, mushrooms, etc.